policy

Dirk Bogarde and Silvia Syms in Victim (Image credit: BFI)

House of Lords

5 June. 1968.

Dear Mr. Bogarde

I have just seen “Victim” for the first time (on telly), and I write to say how much I admire your courage in undertaking this difficult and potentially damaging part. As you may know, I was responsible for introducing the Sexual Offences Bill – now Act – and the swing in popular opinion as shown by the Polls (from 48% to 63% in favour of reform) was largely due to your two films “The Servant” and “Victim”, or so I believe.

It is comforting to think that perhaps a million men are no longer living in fear.

Yours sincerely,

Arran

So reads the text of a letter from the Earl of Arran to Dirk Bogarde, a letter which provides a rarity for anyone investigating the impact of any intervention, cultural or otherwise, on policy: the “smoking gun” of evidence. Watching Victim in 2017 provided impetus for my long-term enquiry into the role that art could play in public policy. It propelled me on a ranging and unexpected journey to find other ‘smoking gun’ examples and to speak with an array of inspiring and unusual characters, from Meow Wolf to Grizedale Arts, from the national security community to Olafur Eliasson. And it inspired me to create Glass House, write two research papers and set up MANIFEST. There’s a full set of resources below, but before that… what have I learnt so far?

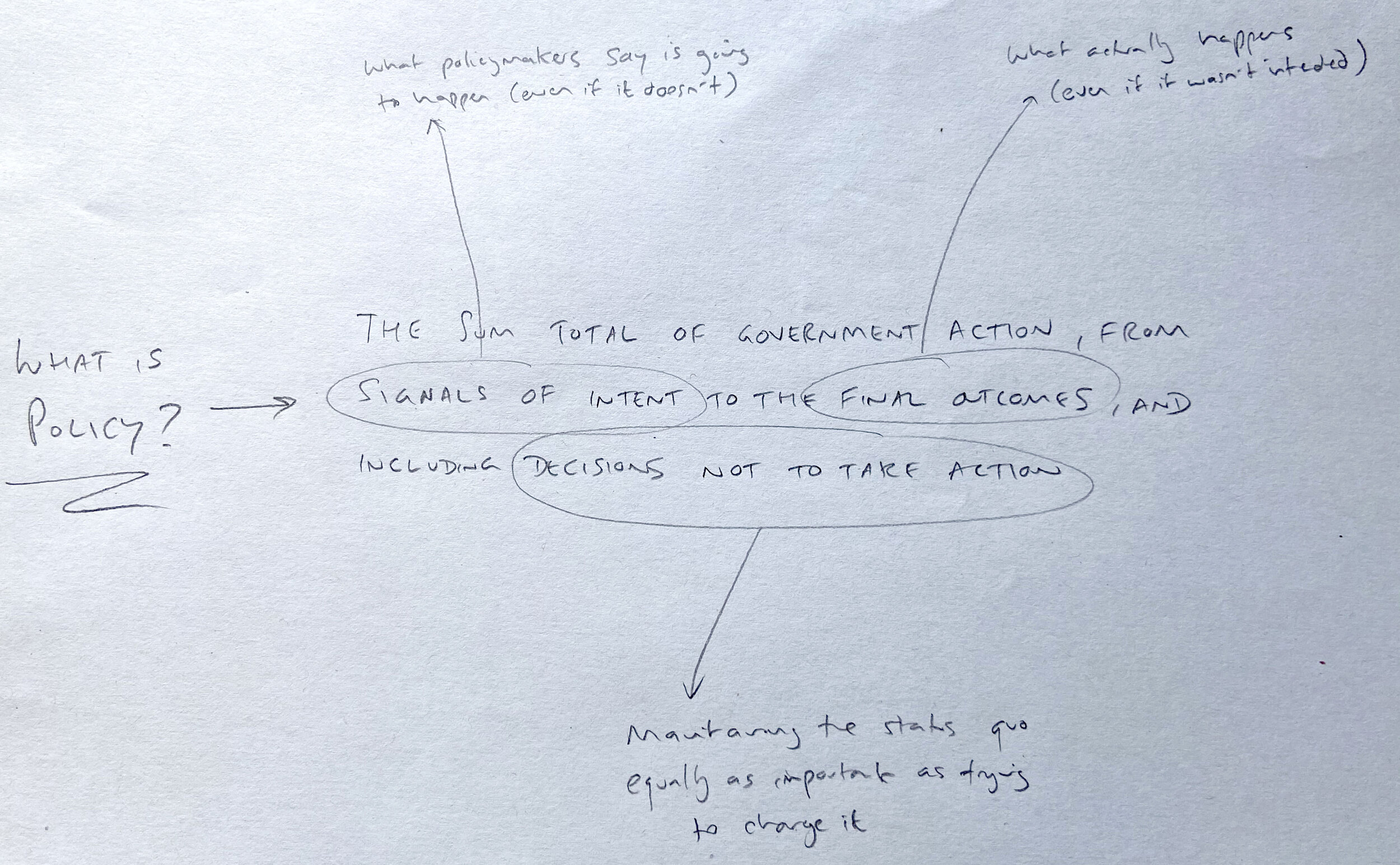

1. Policy is an amorphous concept so a definition can help. Here’s one derived from policy theorist Professor Paul Cairney:

Policy is the sum total of government action, from signals of intent to the final outcomes, and including decisions not to take action.

My notes trying to define policy

2. The BBC’s Blue Planet II acted as a lightning rod unblocking policy decisions on banning certain plastics in the UK. This is based on reasonable evidence, including from a policy professional involved at the time - so is another rare smoking gun example.

3. Thinking about what art can do (rather than what art is) helps understand its possible role in policy. I interviewed Francois Matarasso and found the following instructive from his Parliament of Dreams:

[Art] uses sophisticated techniques [...] to produce intellectual and emotional effects through which it aims to communicate values, ideas and feelings [...] Perhaps most importantly art can question, re-imagine, undermine, critique and dream about existing values and meanings

4. There are (at least) six effects of art relevant for policy. Inspired by Matarasso’s approach, below is a subjective and non-exhaustive list of ‘what are does (that is relevant for policy) - based on my experiences working in policy and practicing as an artist:

A cognitive impact - art can raise awareness of issues and provide information which people may not otherwise have found or be aware of;

An emotional impact relating to a policy matter;

A more-than-text experience of information relevant to policy - for example where policy concepts are instead depicted visually, sonically, physically, and so on;

The creation and manifestation of alternatives to the status quo, where the status quo is defined as the ‘existing state of affairs, especially regarding social or political issues’;

A framing for dialogue and discussion;

The urge and sense of agency to act on an issue.

Vicitim, for example, both raised awareness of issues relating to discrimination, presented policy relevant ideas in a visual and audio way, and had an emotional impact.

5. The ‘policy cycle’ provides a neat, if simplified, overview of how policy is made - and where art might fit in. To look at our examples again, Blue Planet II arguably played a role putting ocean plastics on the public and political agenda.

The Policy Cycle by Paul Cairney (2013)

6. Arte Útil (‘art as a tool’) is a intriguing framing for thinking about the possible role that art can play in policy. The approach, developed by Tania Brughera, Adam Sutherland, Alistair Hudson and others, has informed the ‘useful’ programmes of institutions like Grizedale Arts, the Whitworth and the Middlesbrough Institute of Modern Art. It is worth saying that the originators may not have considered Arte Útil in a national government policy context, and may see complications that are important to address (e.g. who is the art useful for?).

7. ‘Cultural value’ is another useful framework for considering art and policy. Patrycja Kaznyskya, in her 2016 Cultural Value project for the Arts and Humanities Research Council (AHRC), explores the value of culture across different spheres of life including ‘Communities, Regeneration and Space’, ‘Health, ageing and wellbeing’ and, most germanely, ‘The engaged citizen: civic agency & civic engagement’.

8. The Art-Policy Matrix splices Cairney’s policy cycle with the six effects of art relevant for policy, resulting in a 6x6 matrix. I developed the Matrix in the first of two research reports, both produced with support from Clore Leadership and the AHRC and both supervised by Kaznyskya. I populated the Matrix with 21 ‘smoking gun’ examples of art relevant to policy at various stages of policymaking.

9. Kaznyskya helped me understand artistic practice as a form of research. This - retrospectively - provides a unifying theme for the concoction of experimental projects I’ve led over the years combining art, science and policy. Collaborations with the Royal Society, the Government Art Collection, Nesta and the Department for Transport have built an emergent evidence base by learning-through-doing.

10. Glass House is my attempt to recreate Kurt Schwitters’ Merzbau using environmental data and repurposed greenhouse glass - and to continue to learn about the potentiality of art in policy through practice. Once assembled in a crypt in Bethnal Green, I invited groups of five people to spend an hour in the Glass House, consider art and evidence relating to climate change, discuss the materials and articulate ‘what policy needs to happen’. I documented the results in the second AHRC/Clore Leadership report.

Layers of South East Asia (2021), part of Glass House.

11. The New York City Government Public Artist in Residence (PAIR) programme embeds artists in the city government to propose and implement creative solutions to pressing civic challenges. As part of my Clore Fellowship, I visited five PAIR artists including Melanie Crean (Department for Probation), Janet Zweig (Mayor’s Office for Sustainability), Julia Weiss and Kameron Neal (both at DORIS, the Department for Official Records and Information Services). I considered their work in the context of the Art-Policy Matrix for Social Works? magazine.

12. The Artist Placement Group (APG) is something of a British precursor to the New York PAIR programme. The APG was set up by artists Barbara Steveni and John Latham under the Wilson administration of the 1960s. It expanded and negotiated the Whitehall Civil Service Memorandum with the Heath Government of the 1970s, going on to work closely with various government organisations including the Department of Health and Social Security and the Scottish Office. Gareth Bell-Jones, curator at Latham’s archive the Flat Time House, has provided an invaluable link to the history of the APG.

13. At Policy Lab I created and launched MANIFEST, a contemporary programme to bring artists into government, funded by AHRC and working in reference to both the APG and PAIR. The first year brought artists Dryden Goodwin, Christopher Samuel and Semiconductor into three government policy teams. Seeing their work exhibited in Somerset House, policy professionals reflected that MANIFEST demonstrated intriguing possibilities for how art can play a role in policy, including bringing out human elements in the policy system, ‘thinking outside of the box’ in policy development, and making space for and prompting reflection.

Christopher Samuel speaking at an event on MANIFEST at Somerset House

14. Evidence is critical in policymaking, but focusing on evidence alone probably won’t work. Emotions, values and stories are important - this opens a space for art. I developed this idea in a recent Op-ed for the Creative Industries Policy Evidence Centre State of Creativity report based on my own experiences and practice (including this visit to Meow Wolf) and Semiconductor’s embryonic MANIFEST placement in the Government Office for Science:

One of my key values is the importance of evidence in decision-making. But if you ignore other dimensions – emotions, values, preferences and stories – you are setting yourself up to fail. It is not as simple as saying “We have the evidence, so now we need something creative to make people take notice." It is more exploratory, additive and non-linear. It is about the way in which we can engage with evidence in a sensory and dialogical way. And it is an exciting challenge for artists and the creative industries to be involved in.

15. Are artists policymakers? When at Grizedale Arts as part of a Clore Leadership study visit, Adam Sutherland said something which I’ve almost understood a few times, most recently when Christopher Samuel first told me of his plan to write his own Green Paper. In a very special and relevant context - Grizedale Arts is a couple of miles from John Ruskin’s house and where Tania Bruguera developed her manifesto for Arte Útil - Adam delivers a cliffhanger, just before I leave: “you know, perhaps artists are policymakers…”.