I’m often asked by artists and funders how they can ensure the work they are creating can have a policy impact. This article, the fifth in a series on the role of art in policy, sets out some thoughts with reference to three scientific concepts: lability, transference and activation energy.

First, as a reminder, previous articles in this series have set out WHY we might be interested in the relationship between art and policy (article 1); WHAT policy is and why it matters (article 2); HOW art might have different types of effect at different stages of the policymaking process (article 3); and TWENTY EXAMPLES of types of artwork having impacts at different stages of policy (article 4).

Article 4 includes an analysis of Blue Planet II, which both research participants and published evidence suggests had a traceable impact on UK plastics policy, although other political and economic factors may also have been at play. Not everyone can be David Attenborough, but what steps can we take to maximise the policy impact of an artwork, should we wish?

POLICY LABILITY

A work-in-progress shot of the making of Glass House, a participatory art and policy experience developed to test out the concepts articulated in this series of blogs. See more on Glass House here. Image credit: the author.

Lability is a term used in chemistry to describe compounds in which atoms are loosely bound together, and so more easily removed or exchanged. One of the interviewees from my research who works in science and policymaking suggested that, to have a bigger impact, an artwork

“would need to land at a moment where policy is labile… there are moments when [policy] is more open or not”.

If a policy announcement has been made by a minister and a two year delivery plan has just been funded and agreed… it may be difficult to influence this policy. If a new policy issue arises which has not been the subject of party manifestos and is relatively depoliticised, it is likely more labile. In some respects the Blue Planet II example fits with this latter scenario, with the UK plastic straws ban concurrent with the commencement of a 25 Year Environment Plan, changing voter demographics and a Chinese waste import ban including plastics. It is even easier to see with examples like The Museum of Extraordinary Objects, where the Royal Society commissioned artworks to inform a policy position which was explicitly open for development.

TRANSFERENCE

Of relevance here is an important contribution made by François Matarasso in interview (a similar analysis can be found his The Parliament of Dreams essay p7-8). He argued that the search for causality or a controllable connection is fruitless because:

“outside of a totalitarian society, the great strength of art and culture is that it is not controllable. It is beyond anyone's intention”.

Artists and artworks, as well as policymakers and policy, all operate in complex systems where the outcomes are difficult to predict and even harder to control.

In this light, artist and educator Heather Barnett’s use of the term transference is insightful, a concept she described in interview as

"those convergence points where an idea in one realm gets picked up in another in a different way, or one kind of knowledge generation within one realm enables a different interpretation or different direction, in another".

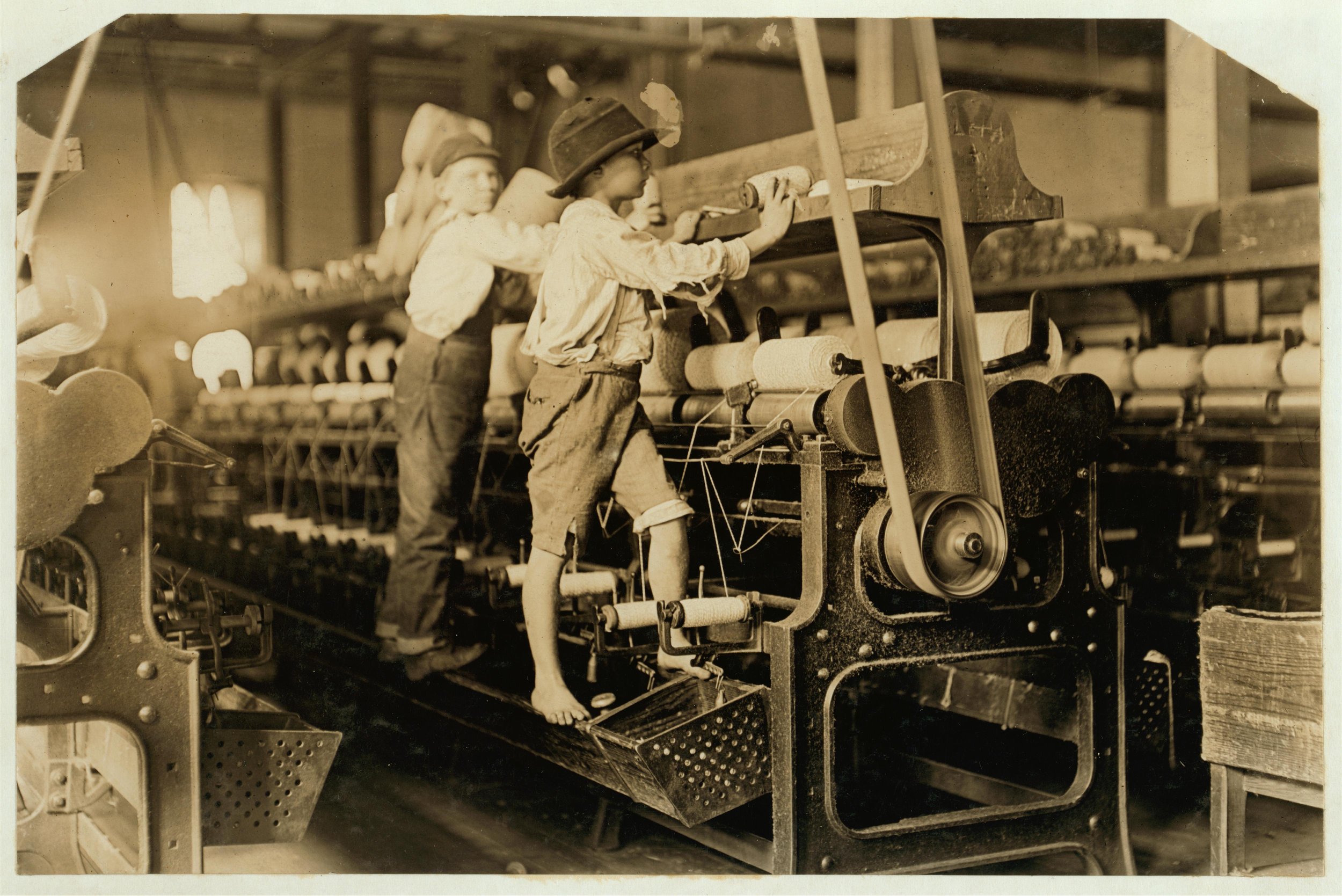

She cites several examples of transference between artistic, technological, societal and political domains, including the microscope, representation and cell theory; gender fluidity and Ursula La Guin’s The Left Hand of Darkness (see image at top of blog); and the promise and concern relating to AI in today’s world. This is a powerful way of thinking about artworks such as William Morris’ News From Nowhere and Lewis Hine’s photography: it jolts us away from tracing causality across days and weeks, and towards thinking about paradigm shifts in society over decades. In the case of Lewis Hine, for example, his turn-of-the-century photography of children in dangerous workplaces (see image below) has been cited as helping bring about US labour laws decades later, most prominently the 1937 Fair Labor Standards.

488 Macon, Ga. Lewis W. Hine 1-19-1909. Bibb Mill No. 1 Many youngsters here. Some boys were so small they had to climb up on the spinning frame to mend the broken threads and put back the empty bobbins. Location: Macon, Georgia. Lewis W. Hine (1909) (Image credit: Wikipedia 2021).

ACTIVATION ENERGY

Imran Khan, in interview, also deploys a chemistry term, “activation energy”, to think about how art may have an impact over a longer time frame. Activation energy is the energy level that two chemicals require to react with each other (e.g. paraffin and oxygen will react at high temperatures, but not if they are both cold). As an example, he notes that much artistic output that goes alongside the Black Lives Matter movement may or may not have specific short term policy objectives now, which may or may not be achieved, but will "lower the activation energy required" for many other, currently unknown, policies in years to come, meaning they are more likely to succeed. Looking back in recent history, Chantal Condron from the Government Art Collection (in interview) identified such a possible relationship between the cumulative work of artists such as Dirk Bogarde, Keith Vaughan and Derek Jarman and half a century’s equalities policy - from the 1967 decriminalisation of "homosexual relations", to the 2003 overturn of Section 28, to the 2010 Equality Act which enshrined certain protected characteristics.

The concepts of transference and activation energy help us understand the entwined, non-linear and profound interaction between art, science and policy over an epochal period in a way which is more nuanced than a scientifically familiar causal evaluation.

SYNTHESIS

We can map the ideas described above to the policy cycle, first described in the third blog (and explained here by Paul Cairney), and combine this with insights from the twenty case studies analysed in the fourth blog. This gives a set of speculative findings which I have tried to illustrate with the following diagram, and have then explained in the bullet points below.

The key points in relation to this diagram are as follows:

It appears easier to evidence impact on more specific, practical examples such as arts in criminal justice, Policy Lab’s Manual for Streets, the future of ageing speculative design, the Waste Isolation Pilot Plant, and the Museum of Extraordinary Objects (read more about these case studies here).

These examples tend to be orientated towards the "how" of policymaking, including policy formulation, legitimation and especially implementation, rather than the "what" of policy-agenda setting.

The outcomes are in many cases "intermediate" rather than "long-term" - for example there is evidence that the Museum of Extraordinary Objects did lead to a development of better policy ideas, but it is tougher to evaluate if the artwork led to better research culture, or whether research culture was even worth focusing on at all.

In contrast, examples such as the art of Black Lives Matter, Lewis Hine, the art of ACT-UP, News from Nowhere and Blue Planet II have a bigger audience and potential impact, but are harder to evidence - though possible (see these case studies here).

These examples tend to be towards the "what" of policymaking, including agenda setting, evaluation (of whether the policy status quo is satisfactory) and policy maintenance/ succession/ termination, where there is a larger window for impact. This potentially takes us towards the concept of transference, as described above.

Based on the case studies considered, one can suggest that there is a possible inverse relationship between magnitude of impact and ease of tracing impact with stages of the policy cycle - as mapped out along the slope shown above.

An image from Policy Lab’s collaboration with the Department for Transport and Chartered Institute of Highways and Transportation, to use multisensory artistic media to enquire into the uptake and use of the Manual for Streets street design guidance in England (image credit: Policy Lab)

In summary, whilst some literature and interviews emphasise the difficulty of finding causality, other statements and observations from the case study analysis suggest evidence can be found in some situations. It is perhaps helpful to differentiate between types of impact, over longer and shorter time periods, with different ramifications in terms of social outcomes. Perhaps the inevitable next question is: “can we develop a toolkit to capture this”? I’ve had a think about this, and may blog about this in the future…