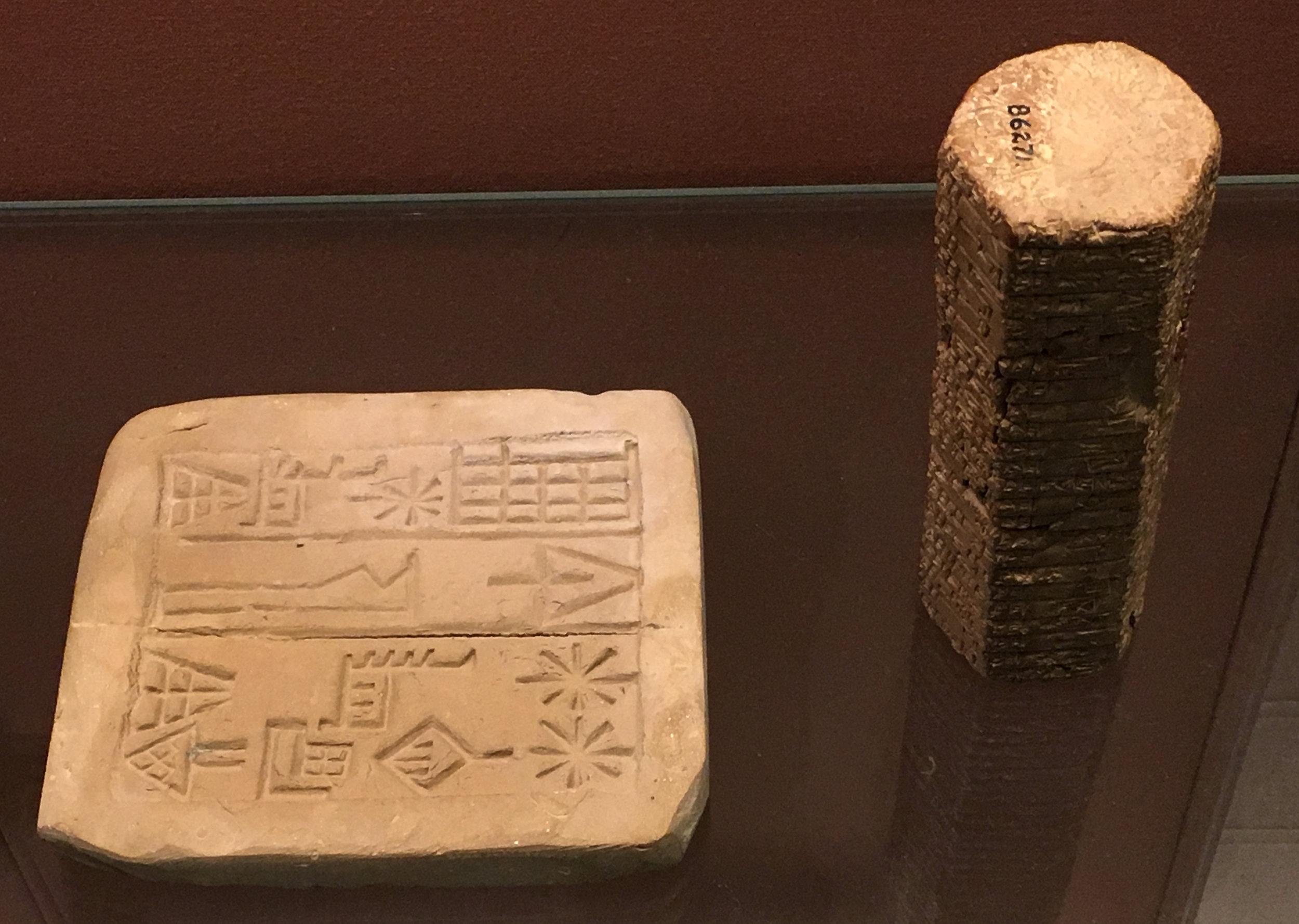

This blogpost provides information on experiments I have conducted with the objective of imposing digital information (imagery, writing, data) onto clay. This process has been central for my art installation in the Central St Martins degree show. Read more about the installation here and the MA Art and Science degree show here. The ambition has been to developed a modern-day version of the ancient Babylonian cuneiforms, using digital data on geology and geography. This is an echo of how the Babylonians first developed writing, which was initially a bureaucratic practice to keep tabs on information relating to the land and settlements. Before getting to the modern stuff, here are pictures of these beautiful cuneiform tablets, at the British Museum:

Babylonian clay cuneiform tablet, the British Museum.

Babylonian clay cuneiform tablets, the British Museum

Laser etching onto clay

My first effort involved using a laser cutter to directly etch onto clay. I worked with CutLaserCut studio in Camberwell, a great team who I highly recommend, to try laser etching onto three different types of clay:

Kiln fired clay, properly known as ceramics

Fully dried clay, known as greenware. Clay must be in this form before it can be fired; it is bone dry, but quite soft at this stage.

Wet clay – in a similar state to how it comes out of the bag.

Laser etching onto kiln-fired ceramic

The results are shown in the photos. On the one hand, there is a discernible mark, and it could be used in some really beautiful constructions (I particularly like the clear edge of the laser mark juxtaposed with the organic cracks and creases of the wettest clay). On the other hand, it is very superficial – nowhere near as deep a score as I intended to echo the Babylonian’s works.

Wet clay, laser etched (and then dried)

There are a couple of additional caveats which meant I ruled out this approach. Most importantly, CutLaserCut had to use their most powerful setting to achieve the mark we got. This translates into considerable laser time, meaning high energy consumption and high costs. Secondly, intriguingly (but irritatingly), it didn’t seem to matter whether the clay was kiln fired or wet; the laser struggled equally to get penetration.

Laser etching on 'greenware' (bone-dry clay which has not been fired in a kiln).

Laser etching onto earth

Part of my degree show installation involves digging up earth from the fields, forests and settlements of the south-east. I wanted to impose digital information onto these materials as well as the shop-bought pure clay (used in the above photos). I returned to the good folk at Central St Martin’s Digital Fabrication Bureau to carry out my next set of experiments. We tried laser cutting onto dug earth – which likely has a reasonable clay content, as it came from Chingford, a very clayey area. Again I achieved an interesting result here, a very noticeable score or burn mark giving a very visible line. This was still not the deep cut I was after to echoed the cuneiform ‘wedge’ shape, so I had to move on.

Laser etching onto dug-up mud, likely with a reasonably high clay content (and yes that is a LEGO figure).

Laser etching into a mould

Working with the CSM casting experts, I identified another approach could be to impose a negative digital imprint onto a cast, which would then transfer onto the clay/earth as a positive. I tested this out first myself carving into a wood block and printing onto the back of the Chingford clay. Whilst the results are crude, they are promising - the indentation has transferred itself onto the clay.

Carving into a mould to create an indentation in clay.

I learnt that plaster would be the ideal material as it would result in the cleanest surface interface with the clay. Could I laser etch into plaster? Yes, with excellent results. In the image below, the word 'Stephen' and the oval, rectangle and diamond have all been created with the laser cutter. There is one, major caveat. Again the laser cutter needed to be on full blast - again massive energy consumption, wear and tear on the laser, and prohibitive costs - about £90 for a 25x25cm surface (and I needed to do nine of these).

Laser etching onto plaster, as a cast for the clay (this is a photograph taken later on, so excuse the mud).

I next investigated whether I could laser etch a positive into MDF; use the MDF positive to create a plaster cast negative; and then use the plaster cast as a mould to obtain a clay positive. It is certainly possible to laser cut into MDF (see image below). Somewhat surprisingly, this still came out as requiring considerable laser energy - the tricky element was going to the 3-4mm depth that I required to get an imprint onto the clay. The cost would work out similar to laser etching directly onto the plaster.

Laser etching onto MDF, to use as a mould to create a plaster cast negative.

CNC Milling

Through these experiments it was becoming clear the problem was with the laser. Whilst it is create at scoring lines, and cutting through thin material, the energy required for deep lines was both unsustainable and costly. I tried a different approach - using a digitally programmed drill bit, otherwise known as the CNC miller (or router). The advantage here is that we are programming a physical implement to carve away at the plaster, rather than a laser to fire energy at a surface. After a couple of tests, I programmed the CNC miller to create a digital map on a 30cm2 block of plaster (using the block I had originally tested the laser cutter on):

The plaster being milled...

The resulting plaster cast

Using the CNC milled-casts

At this point it was now just a question of using the casts as in any ceramic project. I sought expert advice from the amazing team at Leyton's Turning Earth ceramic studio, and filled the casts with either sanded buff clay (straight from the bag), or, at home, with the earth I had dug from nine parts of London (see here for more on that, and the picture below tells a story about the state of our house over the last few months).

Using the mould (for both clay and earth)

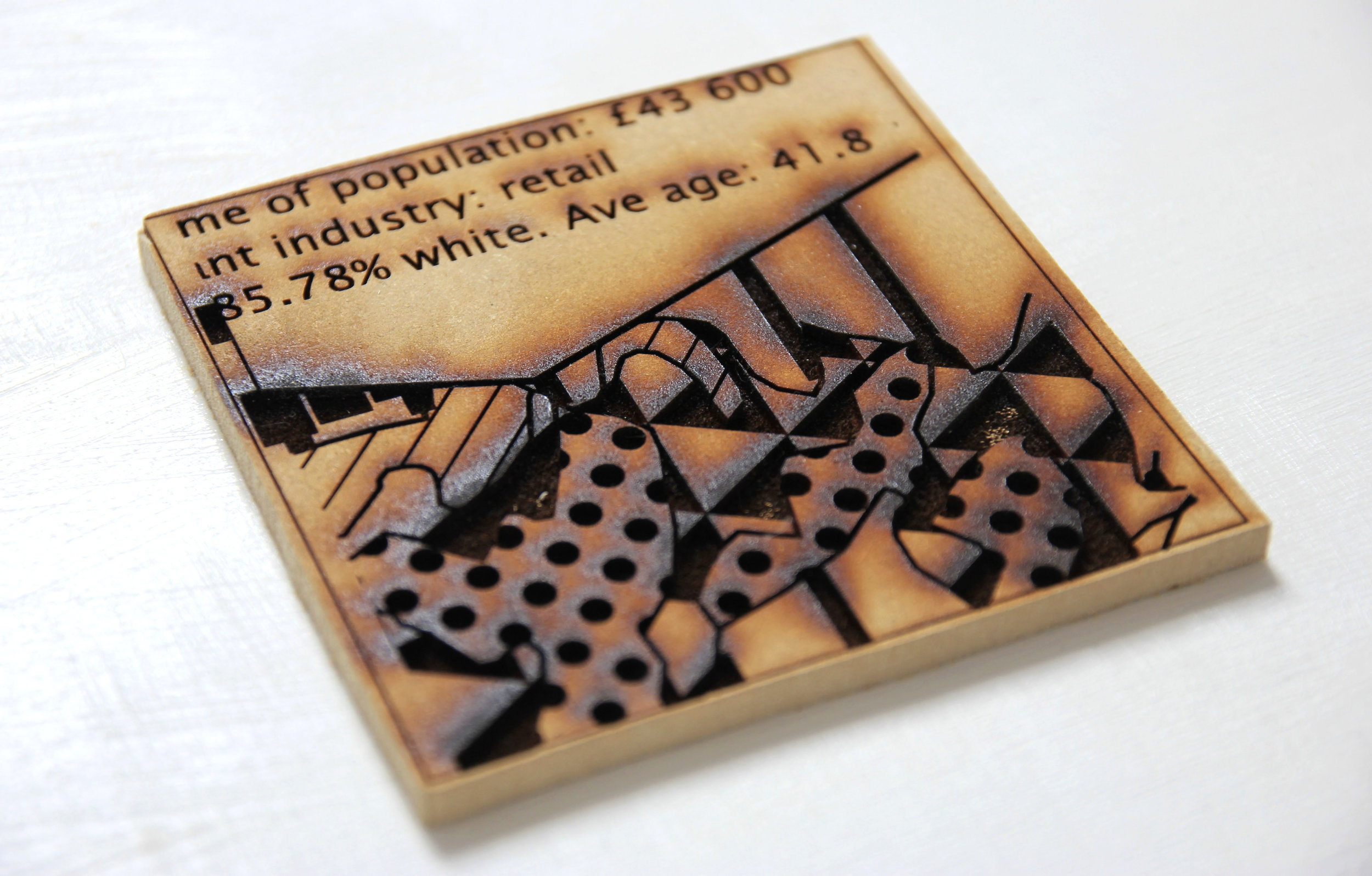

Finally - with a nervous wait whilst the kiln heated and then cooled - I achieved a perfectly formed, modern and digitally fabricated clay tablet (along with a few that exploded in the kiln):

A digitally fabricated clay tablet - the modern take on a Babylonian classic.

I hope you enjoy this blog & find the techniques interesting. Drop me a line if so.